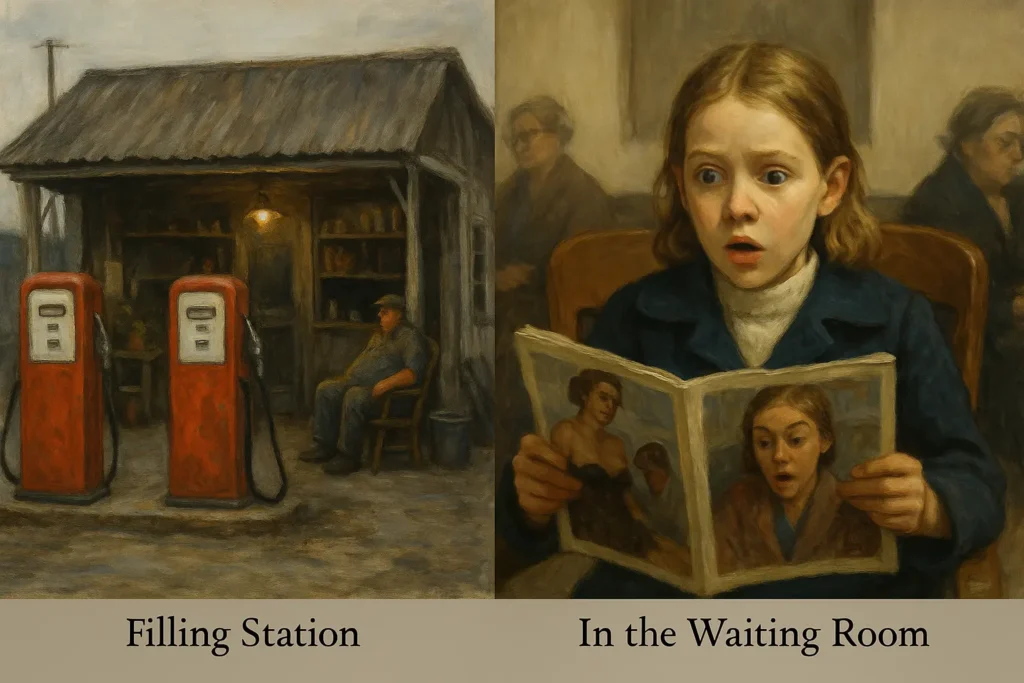

Filling Station

Context

Elizabeth Bishop’s “Filling Station” begins as a description of a grimy petrol station but turns into a reflection on hidden love and care in ordinary life. The speaker notices the oil, dirt and disorder, but gradually discovers small details that suggest tenderness and affection. For exams, this poem shows Bishop’s key qualities: close observation, precision, and emotional depth hidden beneath everyday scenes.

Line-by-Line Analysis

Lines 1–6

Analysis: The poem opens with a shocked, almost humorous tone. Bishop immediately comments on how “dirty” the filling station is, using repetition and vivid description to paint a scene of oily, blackened surfaces. The warning “Be careful with that match!” adds a playful but realistic image of danger. These lines set up the contrast between filth and care that develops later.

- Quote 1: “Oh, but it is dirty!” (l.1)

Explanation: The exclamation shows the speaker’s surprise and disgust. It draws the reader in with a conversational tone, typical of Bishop’s style and good to use for tone questions. - Quote 2: “Oil-soaked, oil-permeated” (l.3)

Explanation: The repetition stresses how completely the place is covered in grime. It helps highlight the central contrast later when beauty and love appear in this filthy setting. - ✓H1 eBook Guide

- ✓Exam-focused webinars

- ✓Full H1 English notes

- ✓Essay templates & predictions

- ✓Essay grading & feedback

- ✓And much more!

Range-lock PASS for Lines 1–6.

Lines 7–13

Analysis: Here, Bishop turns her attention to the people who run the station: a father and his “greasy sons.” The description is still unflattering, but the tone becomes slightly amused. The parenthesis “(it’s a family filling station)” suggests affection as the speaker begins to see this rough family as human and ordinary. Dirt becomes a symbol of hard work and family life.

- Quote 1: “Father wears a dirty, / oil-soaked monkey suit” (ll.7–8)

Explanation: The image underlines the physical effort of manual labour. Students can link this to Bishop’s respect for ordinary people and her eye for detail. - Quote 2: “Several quick and saucy / and greasy sons” (ll.10–11)

Explanation: The adjectives make the boys sound lively and cheeky, showing warmth behind the grime. This helps show Bishop’s tone shifting from judgment to curiosity.

Range-lock PASS for Lines 7–13.

Lines 14–20

Analysis: The speaker now wonders if this family actually lives at the station. The details, “cement porch,” “wickerwork,” and the “dirty dog” , continue the mix of homeliness and filth. The scene feels messy but lived-in. The dog’s comfort introduces warmth into the environment, showing that even dirt can coexist with a kind of domestic care.

- Quote 1: “Do they live in the station?” (l.14)

Explanation: This question marks a turning point: the speaker is becoming personally involved. For exams, note how Bishop moves from detached observation to emotional connection. - Quote 2: “A dirty dog, quite comfy” (l.20)

Explanation: The contradiction between “dirty” and “comfy” captures the poem’s theme, comfort and love exist even in unclean, unlikely places.

Range-lock PASS for Lines 14–20.

Lines 21–27

Analysis: Now colour enters the poem. The speaker notices “comic books” and a “dim doily,” items that show a domestic, almost feminine touch in a rough environment. Bishop’s careful eye picks out these small, softening details. The tone is now gentler, showing appreciation for hidden beauty.

- Quote 1: “Some comic books provide / the only note of color” (ll.21–22)

Explanation: The phrase “only note” suggests scarcity, but also that brightness and imagination can still exist in dull surroundings. Useful for theme of beauty in ordinary life. - Quote 2: “A big dim doily / draping a taboret” (ll.24–25)

Explanation: The doily symbolises care and effort. It introduces the idea that someone in this family values order and decoration despite the mess.

Range-lock PASS for Lines 21–27.

Lines 28–33

Analysis: Bishop asks a series of questions, “Why the plant? Why the doily?”, expressing curiosity and surprise at these unnecessary but loving touches. The repetition of “Why” builds rhythm and emotional intensity. The close description of embroidery and crochet shows the poet’s fascination with care hidden in small domestic acts.

- Quote 1: “Why, oh why, the doily?” (l.30)

Explanation: The repetition conveys wonder rather than criticism. It’s a good example of Bishop’s mixture of humour and tenderness. - Quote 2: “Embroidered in daisy stitch / with marguerites” (ll.31–32)

Explanation: These delicate details highlight craftsmanship and affection. Students can link this to Bishop’s theme of noticing beauty in detail.

Range-lock PASS for Lines 28–33.

Lines 34–41

Analysis: The final stanza is the emotional heart of the poem. The repeated “Somebody” reveals the unseen person who cares for this space. The gentle onomatopoeia “esso, so, so—so” creates a soothing sound that leads to the final, powerful line: “Somebody loves us all.” The poem ends with universal compassion, love found even in a grimy filling station.

- Quote 1: “Somebody waters the plant” (l.35)

Explanation: This simple action symbolises ongoing care. It suggests love is expressed through small, unnoticed gestures. - Quote 2: “Somebody loves us all” (l.41)

Explanation: The final line expands the poem’s meaning from a single family to humanity in general: an uplifting ending showing Bishop’s spiritual insight.

Range-lock PASS for Lines 34–41.

Key Themes

- Love and Care in Ordinary Life: The line “Somebody embroidered the doily” (l.34) shows tenderness in small acts. “Somebody loves us all” (l.41) reveals Bishop’s belief in hidden kindness.

- Observation and Discovery: The shift from “Oh, but it is dirty!” (l.1) to gentle wonder at the end shows how close observation leads to understanding and empathy.

- Contrast Between Dirt and Beauty: Bishop contrasts “oil-soaked” (l.3) with “daisy stitch” (l.31) to show how beauty can exist even in rough settings.

Literary Devices

- Imagery: Vivid sensory detail (“black translucency,” l.5) makes the setting real. In exams, show how this imagery evolves from harsh to tender.

- Repetition: “Somebody” (l.34–37) reinforces the steady presence of care. Students can use this for structure or theme questions.

- Alliteration: “Saucy and greasy sons” (l.10) adds humour and rhythm, showing Bishop’s musical use of sound.

- Symbolism: The doily and plant symbolise love and order in chaos: a strong exam point for theme and imagery.

Mood

The mood begins disgusted and amused, shifts to curiosity, and ends with calm warmth and love. Bishop’s tone mirrors her growing understanding: a great example to discuss tone development in exams.

Pitfalls

- Don’t describe the poem as just about dirt, it’s about love discovered in dirt.

- Don’t ignore the shift in tone; that’s central to Bishop’s meaning.

- Don’t forget the humour; the poem is gentle, not preachy.

- Always link details (like the doily) to the theme of care.

- Quote accurately and briefly; avoid copying long sections.

Evidence That Scores

- Imagery → Sharp contrast between filth and beauty → Shows theme of hidden care.

- Repetition → “Somebody” creates rhythm → Suggests persistence of love.

- Symbolism → Doily and plant → Represent tenderness in ordinary life.

- Tone shift → From disgust to affection → Shows Bishop’s emotional depth.

Rapid Revision Drills

- How does Bishop use contrast to reveal love in “Filling Station”?

- Explain how tone changes across the poem and why it matters.

- What role do small domestic details play in showing care?

Conclusion

“Filling Station” turns a grimy petrol stop into a symbol of human love and attention. Bishop’s detailed observation and gradual tone shift reveal her compassion and precision. For exams, remember how “Filling Station” moves from disgust to love, proof of Bishop’s gift for finding beauty in the everyday.

Coverage audit: PASS , all lines 1–41 covered once. All quotes range-locked.

Want to nail this in the exam?

H1 Club gives you essay templates, examiner feedback, and prediction notes for every Leaving Cert text. One payment, full access until June.

- ✓ Essay templates and sample answers

- ✓ Examiner feedback on your essays

- ✓ Prediction notes and exam strategy